Post-Covid New York

How much harm has Covid-19 done to our great cities? And what will urban life look like in the future? As we inch out of lockdown, these questions are increasingly coming into focus. While there are no easy answers, one thing has become apparent by now: the pandemic has acted less as a change agent for cities than as an accelerant of trends that were already well underway. Thus, to make sense of the next decade of urbanization, it is critical for us to understand the undercurrents and tensions that shaped cities leading up to the pandemic.

There is arguably no better place to ponder Covid’s impact and its acceleration of urban trends than New York City. Every great city is, of course, unique in its own ways, but they all face common challenges. And nowhere are these challenges more clearly visible than in New York. After all, it is “the city where the future comes to rehearse,” as former Mayor Ed Koch liked to say. New York’s transformation over the past half-century, from near bankruptcy in the 1970s to Bloomberg’s luxury vision of the 2000s, offers important lessons for cities and knowledge hubs around the world.

So what are the main lessons from New York’s evolution, or devolution, depending on your viewpoint? Three recent books—one published this year, the other two in 2017—attempt to answer this question by making sense of its modern history. Each one is wildly different in approach and style, but taken together they offer a comprehensive overview of a city that resists easy comprehension. This piece is a synthesis of the lessons and insights that stood out to me. To narrow down the scope, I have adopted a Manhattan-centric view of New York that glosses over the outer boroughs. They would surely merit a long piece of their own.

New York, New York, New York

The latest addition to the New York canon is Thomas Dyja’s New York, New York, New York. It is an engrossing, wide-angled account of the personalities, policies, and cultural developments that have shaped Gotham over the last forty years. One of the real challenges of writing about New York is finding a language that does justice to this high-powered city. NYx3 is a stellar achievement in this regard. Dyja’s dazzling, propulsive prose captures the ebullience and vivacity of New York brilliantly. The whole book pulsates with New York-style energy; in fact, it reads very much like a subway express train blasting through the underground of Manhattan. I found it to be as absorbing and evocative as Robert Caro’s The Power Broker.

Dyja identifies three distinct phases in New York’s remarkable trajectory as it was coming out of the dirty and decrepit 1970s. The first phase, Renaissance, began with the election of the voluble Ed Koch in 1977 and continued throughout the 1980s. Under Koch’s leadership, the city regained its financial footing, entered into a construction boom that gave us Trump Tower, and cruised through the greedy yuppie era of Bonfire of the Vanities. The Reagan years failed to provide a path to shared prosperity, though, which meant that New York was splitting apart economically. Meanwhile, the scourge of AIDS, crack, and crime tore at the fabric of the city. The failures of leadership under one-term Mayor David Dinkins created the pre-conditions for the second phase in New York’s evolution––the safe streets and dotcom excesses of Rudy Giuliani’s Reformation. Then came 9/11, which left many New Yorkers disoriented and receptive to a new mayoral agenda. Terrorism and dotcom recession set the stage for the city’s third iteration: Michael Bloomberg’s controversial Reimagination of New York as a “Luxury City” for the conspicuous consumer. This vision has survived the two mediocre terms of Mayor Bill de Blasio.

According to Dyja, New York’s passage through Renaissance, Reformation, and Reimagination has resulted in “a city flush with cash and full of poor people, diverse but deeply segregated, hopeful yet worryingly hollow underneath the shiny surface.” To be fair, New York is in many ways a better place than forty years ago, even when taking into account Covid-19: it has become richer, cleaner, greener, safer, and generally better groomed. Crucial to the city’s comeback were the 3.6 million immigrants who have come through since 1978 (1.5 million of whom have stayed). But problems of affordability have left the people of New York fragmented. Today, more than 20% of New Yorkers are “severely rent-burdened,” which means they pay at least half of their income on rent. Another 20% spend a third of their income or more on housing. The story of New York is, thus, a tale of two cities––one rich beyond measure, the other increasingly unable to make ends meet. Much has been lost:

“The city of our memories, that thrilling cesspool where anything could happen,… that city seemed to have slipped under a sea of gold. The rich were no longer rich; they were imperial. Chain stores devoured mom and pops. Camp had been domesticated; rage, sex, and high art defanged, rents out of reach, the N.Y.P.D. an army. Hip Hop was mainstream, but the Twin Towers were nowhere to be found. Depending on your mood, your age, your bank account, New York was now horrifying, or wonderful, and even that changed day-to-day, moment-to-moment.”

To his credit, Dyja doesn’t jump to easy conclusions. He looks at the city from all viewpoints, which allows him to get past the binaries, buzzwords, and truisms that tend to shape our discussion of urban transformation. His book hammers home the point that it wasn’t a single policy, person, or party that can be credited with or faulted for New York’s metamorphosis. Instead, it was a combination of structural changes in the economy and inflexible policy choices that were applied to a place in constant flux.

By the late 1970s, New York had begun to successfully reinvent itself as a post-industrial, knowledge-driven economy. While this allowed the city to enjoy years of high growth, it also made it vulnerable to the booms and busts of the FIRE sector (finance, insurance, and real estate). Over the decades, New York became stronger and more prosperous, neighborhoods gentrified, property values skyrocketed, but the benefits didn’t trickle down to all sectors of the urban economy. Wealth became more and more concentrated among a smaller cohort of New Yorkers. These structural shifts were amplified by policies that were put in place to help, but which often harmed those who were most vulnerable: Jane Jacobs-style urban preservation turned into hyper-gentrification; article 421-a of the property tax code induced landlords to add “poor doors” to luxury buildings; and proactive policing escalated into stop-and-frisk, which disproportionately targeted young men of color. Meanwhile, the housing emergency left more than 60,000 homeless. All of this didn’t happen overnight; it was decades in the making and the consequences were often unintended.

The transition from industrial capitalism to a knowledge-based economy also changed the inner workings of New York. A recurring theme throughout the book is how people build networks and connect in cities. Those of you who have read The Power Broker will recall that the old New York was governed by a complex power pyramid that saw Robert Moses and the Rockefeller family ruling at the top. Caro’s tome includes a wonderful chapter, titled Leading Out the Regiment, which describes all the city’s economic interests that formed the base of this pyramid: the bankers, the union leaders, the politicians, the Catholic Archdiocese, and so on. Through the power and money of his public authorities, Moses was able to mobilize these interests into a unified force that he could corrupt and control. This is not how the city ticks today. Dyja argues that over the past half-century, New York has evolved from a city of networks into a networked city that works much like a giant brain:

“Until the ’70s, political scientists described New York as a game played by all its interests with City Hall as the referee. But as Information took over from Industry, the collective world of unions, borough machines, the archdiocese, and even the Mob gradually gave way to one of individuals who define themselves primarily by the networks they belong to… Those with the most connections—and therefore the most access to favors, advice, job tips, and string pulling—shone the brightest… Those without wide connections, or with none at all, were left behind.”

Cities exist to let people form networks, but there is also a darker side to the impetus of humans to connect: social networks are inherently unfair and exclusionary. The reality is that birds of a feather flock together, whether that is yuppies in the 1980s or techies today. In addition, the denser and more high functioning your network, the more financial and social capital accrues to you over time. The same is true vice versa: less density and failing institutions translate into a more fragile community with fewer ties to the rest of the city. This insight holds one of the keys to why New York has split apart: “Wealth in New York does trickle down, but not in a rational, even shower of largesse; it travels through networks of Who You Know—who’s your hairdresser, your wallpaper guy, your dermatologist?—while leaving out those who aren’t in networks.”

Another transformation that profoundly impacted New York was the increasing use of business principles to run City Hall. Back in the 1970s, the city had lost control not just because of debt, but also because it had failed to computerize its accounting. The budget was completely unauditable and no one at City Hall knew how many people the city employed. Koch had to make the place function again. With the help of the bi-annual “Mayor’s Management Report,” he improved accountability and began managing for results, thereby changing the mayor’s job into something closer to a CEO’s. In the early 2000s, the Bloomberg administration took this approach to a whole new level by pioneering what Julian Brash has called “the Bloomberg Way.” This technocratic approach to urban governance envisioned the mayor as CEO, businesses as clients, citizens as consumers, and the city itself as a product that is branded and marketed as a luxury good. The results were a mixed bag. By casting New York as a private corporation, Bloomberg succeeded in making City Hall more entrepreneurial and innovative, but he was unable to serve the interests of the city as a whole. When he left office in 2013, the homeless shelter population had grown by 61% and a staggering 85% of New Yorkers complained that the city had become too expensive to live in.

In Dyja’s view, a fourth evolution of New York is now imminent. The pandemic, the economic and fiscal fallout, as well as movements for racial justice are forcing this change. So does the mayoral election in November. Post-Covid New York needs economic growth more than ever, but it also needs what Dyja calls citymaking: the active, daily participation of its citizens to re-energize the city and make it more inclusive. He believes that too many New Yorkers have become passive consumers of urban life and that democracy demands more of us than just voting, shopping, and complaining. His prescriptions invoke the spirit of the great urbanist Jane Jacobs, who said: “Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.”

While I agree with the general premise of Dyja’s proposals, they are too abstract to offer guidance on a practical level. This is a clear shortcoming of an otherwise excellent book. To me, the real leverage lies not in grassroots movements but in further refining “the Bloomberg Way.” In the Information Age, the government must urgently evolve from a monolithic service provider to an entrepreneurial system that steers instead of rows. As Mario Cuomo, the former Governor of New York, once put it, “it is not government’s obligation to provide services, but to see that they’re provided.” I personally share Michael Bloomberg’s belief that City Hall should be accountable to its customers, rather than to internal bureaucracies, for the results it delivers. It’s just that tourists and foreign oligarchs are not the only customers of New York, and that the amount of tax revenue a city generates can’t be the only measure of success. Bloomberg’s overwhelming focus on global competitiveness came at the cost of distributional considerations. The incoming mayor would do well to correct this deficiency.

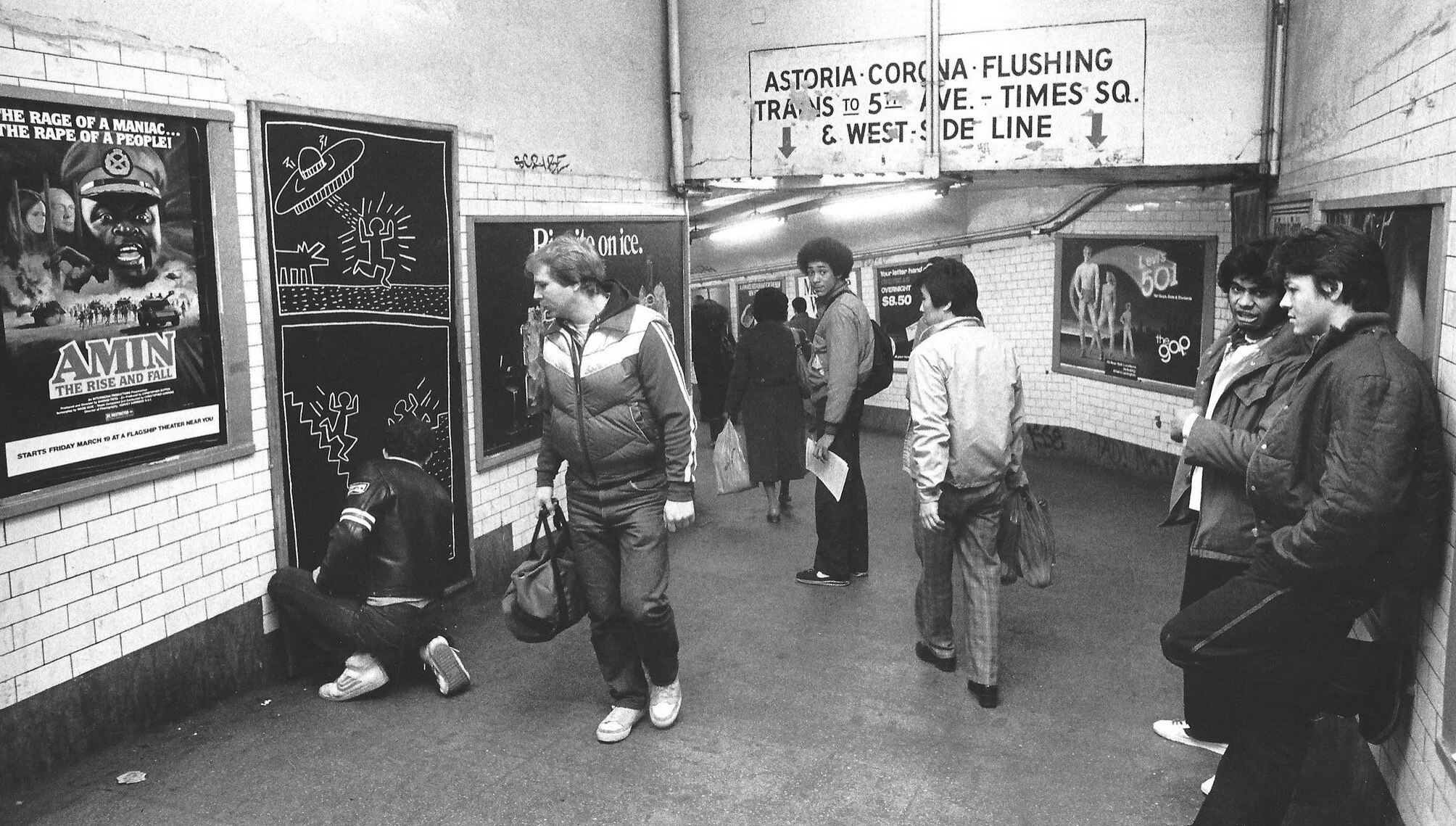

Art in Transit: Keith Haring drawing in a New York subway station in 1981.

Vanishing New York

A very different kind of book is Vanishing New York by Jeremiah Moss. Since 2007, Moss has chronicled the physical and spiritual casualties of gentrification on his feverish blog of the same name. Ten years in, he synthesized his worldview in a book that is righteously indignant and bitterly nostalgic. Moss laments that a relentless monotony of chain stores, luxury condos, and bland high-rises has turned Manhattan into a theme park for the global super-rich. He strongly echoes Adam Gopnik’s observation that “New York is safer and richer but less like itself, an old lover who has gone for a face-lift and come out looking like no one in particular. The wrinkles are gone, but so is the face.” If the city was a work of art, its artist would surely be Jeff Koons: shiny on the outside, hollow on the inside; in a word, soulless.

So far, so good. Moss offers some deep reporting on Manhattan’s changing texture that is well worth reading. He also identifies a set of important problems that afflict many great cities: the crowding out of artists, bohemians, and deviants who provide cities with creative ferment; the washing out of small local businesses whose storefronts are replaced by yet another Starbucks, Walgreens, or 7-Eleven; and the increasing homogenization and suburbanization of urban spaces, which has created a “geography of nowhere.” Moss faults soaring rents and an unconscionable housing shortage for these problems, but the issue runs much deeper for him: not only has the city changed, but the nature of urban change has changed. While it remains to be seen whether Covid-19 will reset rents permanently, it is fair to say that lower Manhattan and parts of Brooklyn have lost some of the vibrancy and authenticity they used to have.

Unfortunately, Moss is too consumed by wrath and embitterment to treat these issues with any sense of nuance. He frequently tips into hyperbole when describing the profound shift he sees in the everyday psyche of the city: neoliberal policy is described as “a toxic plague on New York’s soul”; gentrifiers are cast as one-dimensional villains who are conspiring with landlords to drive out Bohemia; former Mayor Rudy Giuliani is berated as “the Mussolini of Manhattan”; squalor and low-life culture are romanticized to the point where they bear little to no resemblance with reality; and the alleged demise of New York is “not just the story of a death; it’s the story of a murder.” Worse still, the author’s contempt for tourists and transplants frequently drifts into the ad hominem.

I should point out here that Jeremiah Moss is a pseudonym. It is the nom de plume of Griffin Hansbury, a New York-based psychoanalyst and activist who has described his cantankerous writing style as follows: “If you took the crankiest part of me and isolated it, it would be him.” I’m afraid this kvetching attitude sadly undermines the whole integrity of the book’s reporting. Writing a 450-page rant may have been cathartic for the author, but it will test the patience of even the most sympathetic reader. This is a real shame because Moss speaks for so many people who feel increasingly unwelcome in the cities they call home. It is a terrible feeling to have and it deserves to be taken seriously. We all have some skin in the game here. As the late Christopher Hitchens has written, “on the day when everywhere looks like everywhere else we shall all be very much impoverished, and not only that but—more impoverishingly still—we will be unable to express or even understand or depict what we have lost.”

The sentiment of loss and displacement that Hitchens alludes to is at the heart of Moss’s orgy of reminiscence. He yearns for the good ol’ days when New York was sexier, edgier, and its sidewalks littered with dog shit. But this excessive, rose-tinted fixation on the past is not without dangers. The problem with nostalgia is that it is rarely accurate and often tremendously distorted. Moss is particularly adept at screening out the bad: he makes only passing reference to the “Bronx is Burning” years that left entire neighborhoods “Dresden-ized”; he has no recollection of the terrible blackout of 1977 that plunged nine million people into darkness and unleashed the city’s demons; he ignores the spiraling crime and murder rate that made it unsafe to leave your home after dark; he glosses over the harrowing AIDS crisis that killed 50% of Manhattan’s gay Baby Boomers; I could go on but you get the idea. Not everything was wonderful and not all changes were bad. The past that Moss romanticizes was demonstrably unlivable for many and an Eden for only a select few. But still, he prefers the faux certainty of the past over the uncertainty of tomorrow. This is a worldview I’m very much against. We need to reimagine our great cities, not just rebuild them.

Sleazy and dirty: Times Square in 1977, before it became a “Disneyfied” tourist destination.

The New Urban Crisis

The final book of the trio is Richard Florida’s The New Urban Crisis. Florida emerged as one of the most influential urban theorists two decades ago with his bestselling book, The Rise of the Creative Class. In it, he correctly argued that urban fortunes would turn on the capacity to attract and retain members of the so-called “creative class”––a group that includes high-skilled entrepreneurs, professionals, creatives, and the like. He predicted that clustering them together would become the key driver of urban growth and that capital would follow talent, not the other way around. Florida’s observations shaped urban policy in many places, including New York, while also attracting strong academic criticism. His latest book, published fifteen years after the first, is a sobering account of what the clustering of creative talent has done to cities. While not about New York per se, it relies heavily on examples from the Big Apple to illustrate the structural forces that are shaping cities today.

Florida’s core thesis is that “superstar cities” like New York have become victims of their own success: “Although clustering drives growth, it also increases the competition for limited urban space; the more things cluster in space, the more expensive land gets; the more expensive land gets, the higher housing prices become, and the more certain things get pushed out.” In other words, attracting the creative class and governing “the Bloomberg Way” has come at the expense of less advantaged urbanites who are being elbowed out by rising costs. This is the great paradox of the “clustering force” of talent and innovation: it is at once the main engine of economic growth and the biggest driver of urban inequality. The rise of remote work due to Covid-19 is unlikely to reverse this dynamic anytime soon. In fact, economic inequality and spatial segregation are likely to harden over time:

“As the advantaged groups colonize the best neighborhoods, they gain access to the most economic opportunities, the best schools and libraries, and the best services and amenities—all of which compound their advantages and reinforce their children’s prospects for upward mobility. The less advantaged are shunted into neighborhoods with more crime, worse schools, and the dimmest prospects for upward mobility. Simply put, the rich live where they choose, and the poor live where they can.”

The result of this escalating competition for urban space is that New Yorkers are increasingly segregated by income, education, and class. But dividing city dwellers into villains and victims is not as straightforward as the quote suggests. The strength of Florida’s book lies in its use of economic data to separate myth from reality. This makes it an excellent complement to the other two books. For example, he acknowledges that gentrification is a wrenching feature of cities, but stresses that the media’s obsession with the topic deflects attention from the far more serious problem of urban poverty. He further contends that the ultra-rich can hardly be as damaging to Manhattan as Jeremiah Moss asserts: “There are simply not enough super-rich people to deaden an entire city or even significant parts of it… 116 billionaires and 3,000 or so ultra-high net worth multimillionaires wouldn’t fill half the seats in Radio City Music Hall.” Never mind that the top 1% of New Yorkers pay close to 43% of the total income tax the city collects. The same extends to techies and startup companies. Florida concedes that they are putting pressure on urban real estate, but clarifies that they are not the primary drivers of inequality (though they surely contribute to it). Urban poverty doesn’t stem from poor neighborhoods getting richer through gentrification, but from poor neighborhoods staying poor, generation after generation, without access to good schools, jobs, parks, transport, and networks.

The book ends with a series of policy prescriptions that aim to make the creative economy more inclusive. As one would expect, most of the policies address the shortage of affordable housing. Florida cautions against the deregulation of land use and urges policymakers to redirect federal housing subsidies from affluent homeowners to urban renters. He also advocates for a land value tax to create incentives for property owners to put urban space to its most intensive use. But solving the housing crisis is not as straightforward as one would hope. According to a recent paper by two reputable economists, building more urban housing would not automatically translate into lower prices. In fact, it could very well increase housing prices by attracting more members of the creative class. In that context, the paper advises addressing the root cause of the affordability problem, namely the collapse of the “urban wage premium” for less-educated workers, rather than trying to cure the symptoms with imperfect policies. Unfortunately, Florida’s book provides us with few pointers on how to solve this puzzle.

Another area that New York must invest in is public transport. The high cost of living would certainly be less of a problem if the city’s 116-year-old subway system wasn’t in such a terrible state. This is one of the most urgent problems the new mayor must confront. You don’t have to read The Power Broker to know that mass transit plays a vital role in the daily functioning of New York. It provides both physical and social mobility to millions of New Yorkers. But although daily ridership hit 5.5 million before the pandemic, the system has been neglected and underfunded for decades. What is going on here? By a strange quirk of history, the Governor of New York, not the mayor, is ultimately responsible for the city’s subway network. It is he who controls the state budget that funds the MTA. But there is one area of transportation that the mayor has some leverage over: the city’s bus network. After all, it is the city that controls the streets they run on. This is where the new mayor should move first.

Last days of Rome: Hedonism, glitz and glamor at the legendary Studio 54.

New York’s Fourth Evolution

So how does New York’s past inform its future? As we have seen, a number of problems were already festering in the city when the pandemic hit in March 2020. “Covid just lit the match––the TNT has been here for some time,” as one New Yorker put it. It should therefore not come as a surprise that the “New York is dead” essay has found renewed life in recent months. To me, the whole notion of the city’s demise sounds pretty ridiculous. If you look at recent history, the obituary of New York has been written three times in the last twenty years alone: first after the dotcom crash and 9/11, then during the financial meltdown of 2008, and now with the pandemic. New York recovered from the first two crises, and it will surely recover from this one. This time is not different. But there are questions.

One question is whether the rise of remote work will permanently weaken the clustering force in high-cost cities like New York. I’m afraid this is unlikely to occur in a sustained way. Only a small fraction of the workforce will continue to work fully remotely when the pandemic ends. The rest will transition to a more hybrid model, which means the office will shrink, but it won’t disappear. Some people will leave the city, as was already happening before Covid, but places like New York that offer great amenities and opportunities will remain magnets for talent and capital. Young people need cities to build networks, as does most everyone else. And let’s be honest: many of us who have spent the last year in home office have drawn off professional and private relationships that we built face-to-face in pre-pandemic times. The strength of the “weak ties” in our networks will erode over time if they are not replenished. We can’t spend down our social capital indefinitely.

Another question is how New York will look and feel after its fourth evolution. I suspect that much will depend on who is leaving the city and who is moving in. It would certainly be desirable if Covid flushed out some of the suburban dullness that has drained New York of its flavor lately, but that could carry a hefty price tag: according to a recent study by the Manhattan Institute, the departure of only 5% of high-income New Yorkers––those earning $100,000 or more a year––would result in an annual tax revenue loss of $933 million. Bohemia comes at a cost that even the bohemians may not be willing to pay.

Arguably the most important question is how long the elastic band of inequality can stretch before it snaps. The number one lesson I took away from all three books is that persistent poverty and class division are the defining problems of cities like New York. These are problems that few of us experience as we sit around in our comfortable home offices, but they do exist and they are actually growing worse. By accelerating pre-existing trends, Covid has reinforced the advantages of those at the top while at the same time exacerbating the disadvantages of those at the bottom. The creative class will come out of this pandemic with more geographic flexibility, higher savings, and their health intact. On the flip side, essential service workers and the blue-collar working class will continue to confront stagnating wages and declining social mobility. This is a tragedy I can see more clearly now. Solving it will be one of the biggest challenges of our lifetime.